From Canvas to Camera: How Sports Broadcast Transforms Live Football into Moving Art

Premier League matches are watched by billions of viewers across more than 200 territories each season. That global reach depends on cameras, directors, and production crews who shape every pass and goal into a visual story. What if every match wasn’t just played on grass, but painted in motion through light, color, and composition?

Modern Sports Broadcast (스포츠중계) coverage shows how live football can feel cinematic. Platforms such as Royal TV highlight how framing, slow motion, and crowd cutaways guide the viewer’s eye with care. During an EPL Broadcast, directors choose angles the way a painter selects perspective. A high, wide shot sets the scene. A tight close up captures sweat, focus, and emotion. Each decision shapes how the match is seen and felt.

Framing the Pitch Like a Landscape

Long before television, artists like [“people”,”J. M. W. Turner”,”english romantic painter”] used sweeping skies and layered horizons to create depth. Today’s aerial stadium shots work the same way. A camera suspended above the pitch reveals patterns of movement that resemble brushstrokes across a vast green canvas. The pitch becomes a landscape, just as you can see in An art piece made of basketball court, where a court becomes a creative composition. Players become figures moving within it.

Directors rely on composition rules familiar to any art student. The rule of thirds guides where a striker stands before a penalty. Leading lines appear as defenders form a wall. Depth is created when the foreground shows a player in motion while the blurred crowd fills the background. These choices feel natural to viewers because they mirror visual principles that have shaped art for centuries.

Portraiture in Motion

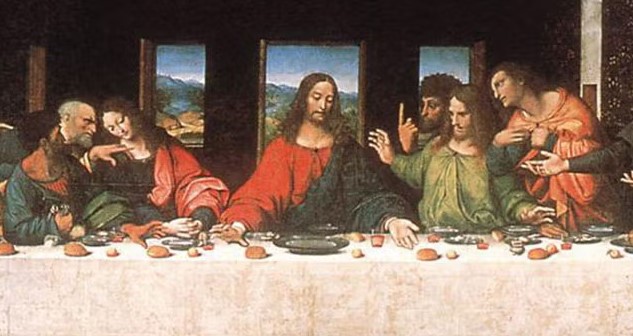

When the camera cuts to a manager on the sideline or a forward moments before kickoff, the broadcast shifts from landscape to portrait. The human face becomes the focal point. Renaissance artists such as [“people”,”Leonardo da Vinci”,”italian renaissance polymath”] understood the power of expression. A raised eyebrow or tight jaw can tell a story without words.

Slow motion intensifies this effect. A replay of a goal celebration, captured at high frame rates, stretches a few seconds into a study of emotion. Every detail stands out, from the ripple of a jersey to the roar of the crowd behind. These moments echo photographic realism. They invite viewers to pause and absorb the drama as if studying a still image in a gallery.

Light, Shadow, and Color

Stadium floodlights do more than illuminate the field. They create contrast. Under bright beams, players glow against darker stands. The effect resembles chiaroscuro, a technique mastered by [“people”,”Caravaggio”,”italian baroque painter”], where strong light meets deep shadow to heighten tension.

Color theory plays its role as well. The vibrant green pitch anchors the frame. Bold team kits, whether deep red or electric blue, pop against that base. Producers adjust color grading to maintain consistency across changing weather conditions. A rainy evening match may carry cooler tones, while a sunny afternoon feels warm and saturated. These subtle choices influence mood without most viewers even noticing.

The Rhythm of Replays and Graphics

Visual art is not always static. Abstract painters like [“people”,”Wassily Kandinsky”,”russian abstract painter”] explored rhythm through shape and color. Broadcast directors achieve rhythm through editing. Quick cuts during a counterattack raise the heartbeat. A delayed replay after a foul slows the tempo and builds anticipation.

Graphic overlays add another layer of design. Scoreboards, player stats, and animated transitions must be clear yet visually balanced. Fonts, spacing, and motion graphics are carefully planned. When done well, they blend into the experience. They feel like part of the composition rather than distractions.

Performance Art Behind the Scenes

Every live match is a coordinated performance. Directors sit in production trucks surrounded by screens. Camera operators track movement with precision. Replay technicians select the perfect angle within seconds. Their work is collaborative and time sensitive. There are no second takes.

This is where sports coverage begins to resemble performance art. The outcome of the match is unscripted, yet the visual narrative is shaped in real time. An EPL Broadcast depends on instinct and experience. The director must sense when to cut to the crowd, when to linger on a player, and when to pull back for context. The result feels seamless, though it requires intense focus and teamwork.

Streaming and the Cinematic Experience

Digital platforms have raised expectations. Viewers now watch matches on large 4K screens and mobile devices alike. High dynamic range enhances contrast. Surround sound captures chants and stadium noise with depth. The modern Sports Broadcast adapts to each format while preserving visual integrity.

Streaming services also allow creative experimentation. Alternative camera feeds, tactical views, and behind the scenes shots expand the artistic palette. Fans can choose how they experience the match, much like selecting a vantage point in a gallery.

Seeing Football as Art

Football remains a competitive sport at its core. Yet the way it reaches audiences is shaped by artistic judgment. Camera composition mirrors classical techniques. Lighting and color set emotional tone. Editing creates rhythm and suspense.

Sports Broadcast deserves recognition as a visual art form. It transforms ninety minutes of play into a carefully composed spectacle. The next time a goal arcs into the top corner, look beyond the scoreline. Notice the framing, the light, the reaction shots. The match is unfolding on grass, but it is also being painted in motion for the world to see.

Read More →

Italy’s rich art history draws modern artists from around the world. Its ancient ruins, Renaissance masterpieces, and vibrant local scenes spark creativity. Many artists dream of relocating to immerse themselves in this inspiring setting. Italy’s allure lies in its ability to blend history with living culture, offering a unique backdrop for reimagining artistic work. Services like Why Wait Italy make this dream attainable, helping artists navigate the legal process of moving abroad.

Italy’s rich art history draws modern artists from around the world. Its ancient ruins, Renaissance masterpieces, and vibrant local scenes spark creativity. Many artists dream of relocating to immerse themselves in this inspiring setting. Italy’s allure lies in its ability to blend history with living culture, offering a unique backdrop for reimagining artistic work. Services like Why Wait Italy make this dream attainable, helping artists navigate the legal process of moving abroad.

It’s called grid harmony when rows have similar tones or storylines. Meanwhile a visual rhythm is when pictures are a good mix of simple and bold, and changing content types (like art, tools, and behind-the-scenes).

It’s called grid harmony when rows have similar tones or storylines. Meanwhile a visual rhythm is when pictures are a good mix of simple and bold, and changing content types (like art, tools, and behind-the-scenes).

Webtoon is an online comic in South Korea that started at the beginning of the 2000s. It is available in black-and-white on the country’s website. However, as technology developed, the webtoon form changed, too. Now, webtoons are defined by their vertical scrolling style, full-color graphics, and often-included sound effects and animation. This development has let webtoons explore fresh artistic possibilities and escape the restrictions of conventional print comics.

Webtoon is an online comic in South Korea that started at the beginning of the 2000s. It is available in black-and-white on the country’s website. However, as technology developed, the webtoon form changed, too. Now, webtoons are defined by their vertical scrolling style, full-color graphics, and often-included sound effects and animation. This development has let webtoons explore fresh artistic possibilities and escape the restrictions of conventional print comics.

To make our point more vivid, let’s take a closer look at the different aspects that make San Jose tow trucks quite reliable.

To make our point more vivid, let’s take a closer look at the different aspects that make San Jose tow trucks quite reliable.

The use of art in Christian worship and practice may be attributed to the Bible’s instructions to “make beautiful” (Exodus 25:31). The Bible also provides examples of artwork in Christian history. These include the mosaic pavement from the first century and the marble statues from the fourth century. Christians have always used art due to biblical instructions, for example, Exodus 25:31, as well as historical examples of artwork such as mosaic pavements from the first century and marble statues from the fourth century. Same goes with churches and Christianity in France. Read Les Trois Deniers de Gaspard’s book about church in France.

The use of art in Christian worship and practice may be attributed to the Bible’s instructions to “make beautiful” (Exodus 25:31). The Bible also provides examples of artwork in Christian history. These include the mosaic pavement from the first century and the marble statues from the fourth century. Christians have always used art due to biblical instructions, for example, Exodus 25:31, as well as historical examples of artwork such as mosaic pavements from the first century and marble statues from the fourth century. Same goes with churches and Christianity in France. Read Les Trois Deniers de Gaspard’s book about church in France. Fashion can express our personalities. Style clothing is not just about looking good, it’s also about feeling confident and comfortable. You should always look at yourself in the mirror and make sure you wear clothes like lacrosse clothing that enhance your body type, personal style, and personality. Let’s find the

Fashion can express our personalities. Style clothing is not just about looking good, it’s also about feeling confident and comfortable. You should always look at yourself in the mirror and make sure you wear clothes like lacrosse clothing that enhance your body type, personal style, and personality. Let’s find the

These are mostly recommendations about clothing ensembles, coordinates or accessories to use in promoting a new clothing line or in dressing up a celebrity or important personality.

These are mostly recommendations about clothing ensembles, coordinates or accessories to use in promoting a new clothing line or in dressing up a celebrity or important personality. Still, effectively combining one’s background in education and experience, with one’s natural talent will go a long way in building a reputation as a fashion stylist in the world of fashion and glamour.

Still, effectively combining one’s background in education and experience, with one’s natural talent will go a long way in building a reputation as a fashion stylist in the world of fashion and glamour. Your letter of application must be accompanied by a curriculum vitae that contains important personal details such as your name, residential address, email address, contact number, educational attainment, professional references, awards and link to your online creative portfolio.

Your letter of application must be accompanied by a curriculum vitae that contains important personal details such as your name, residential address, email address, contact number, educational attainment, professional references, awards and link to your online creative portfolio.